Until Its Last Minute, the Santito/Parka Bloodbath Is As Eternal As Wrestling Gets

Santito and La Parka come as close to emulating the eternal battle between heaven and hell as you can, until human intervention brings them back to earth.

One of the fun things about not really knowing shit about wrestling is when you get to branch out a bit and watch something entirely new. We’ve covered El Hijo Del Santo and La Parka (whose original stylization I’ll be using here as that’s what he was using) on BIG EGG in the past, but lucha libre is still a mostly unexplored continent to me, the shores of which are the WCW Cruiserweight Division that I grew up with and the 2010s-era CMLL/NJPW Fantasticamania tours. Every time we do a lucha libre match it’s like I’m being dropped into a moment of peak emotion, peak heat, something bloody and mean and awful, whose reason for devolving into a legendary bloodbath is likely to remain a mystery to me.

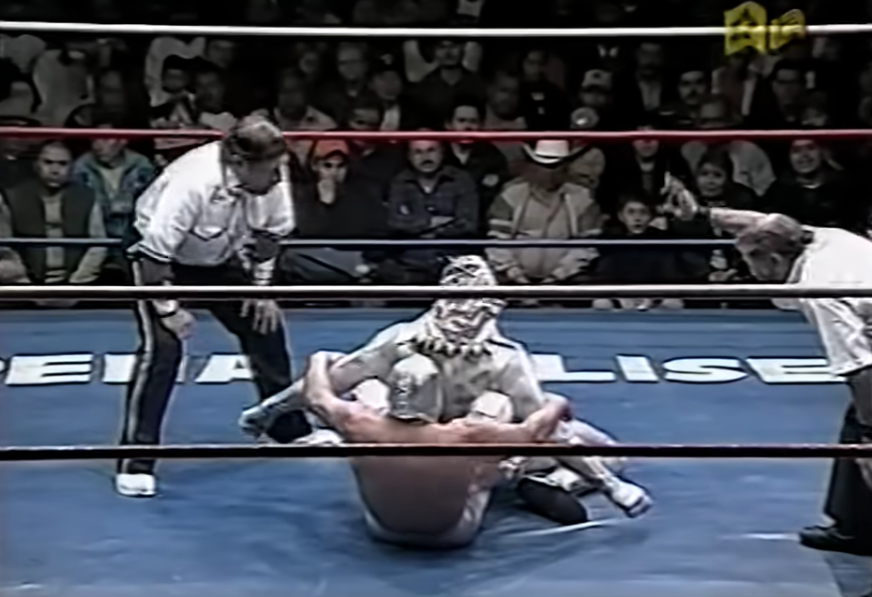

Here’s one of those, where commentary is quick to point out that Santito is the technico and La Parka is the rudo, but it’s Santito who attacks while the referees are still giving their instructions, a man out for vigilante style justice the night before the night before Christmas. He takes La Parka outside immediately, hurling him into the ringpost, hitting him with a DDT, eventually ripping his mask — a silver-and-white variant of Parka’s traditional black-and-white garb, a means of mocking the son of the silver-masked man and his family that will give him a canvas upon which to paint a masterpiece in the technico’s blood. A disagreement with a ringside second gives La Parka a second of respite, but only that: Santito is a heatseeking missile, wrapping the premiera caida quickly with a top rope tope and a camel clutch, forcing La Parka to tap. He is out to embarrass this man in a bone-deep way the likes of which nobody, not even WCW’s creative team, could imagine, and by all accounts it seems like he is going to get his way.

Oh hey — you may be aware of this, but BIG EGG is in the midst of its 2025 Membership Drive — we're trying to get to 100 paid subscribers before the end of the year! To get us there, I'm writing 31 new match reviews in addition to regular BIG EGG business, and the first five are already up — the Funk/Flair and Austin/Hart ones in particular being must read. We're at 85/100 members — help us hit our goal!

Speaking of WCW, one of my favorite assertions of theirs was that it was difficult for luchadors to get over in the United States because the mask made it difficult to read the emotions of the wrestler wearing it. There’s the obvious demographic argument against this (plenty of Mexican wrestling fans live in the United States), but also, man, when the segunda caida begins and Santito is working at the hole he’s opened in the mask and you catch a glimpse of the forehead and curly black mop of hair belonging not to a living ambassador of hell, but to Adolpho Taipa? That’s as human as it gets, as wrestling as it gets. That this is still something American promotions tend to struggle with, either because they don’t get what makes masks so effective or because it’s easier, in 2025, to fast track a program to heat by tapping into the heart of All-American xenophobia, is really unfortunate, as Parka, already selling emphatically from the first blow, really steps it up a notch here, the top of his lid flopping around as Santito continues to beat him, throwing him into the ringpost and out into the crowd at his leisure, controlling his rival by gripping his mask and firing away at the target he himself has opened up. La Parka’s mask being a two part design — a mask with a hood over it — puts in a lot of the work here, flipping to and fro and providing a veil for Taipa to go to work on his own forehead, or so you think. For all of the tapping he does at his own forehead, for all of the telltale signs that a wrestler is running a razor, La Parka's mask doesn't run crimson, and his bodysuit will not get stained until later. It's a red herring, to the point that Santito finds himself focusing on submissions to show the Arena Coliseo crowd his handiwork, presenting a ripped mask to them without any blood on his hands.

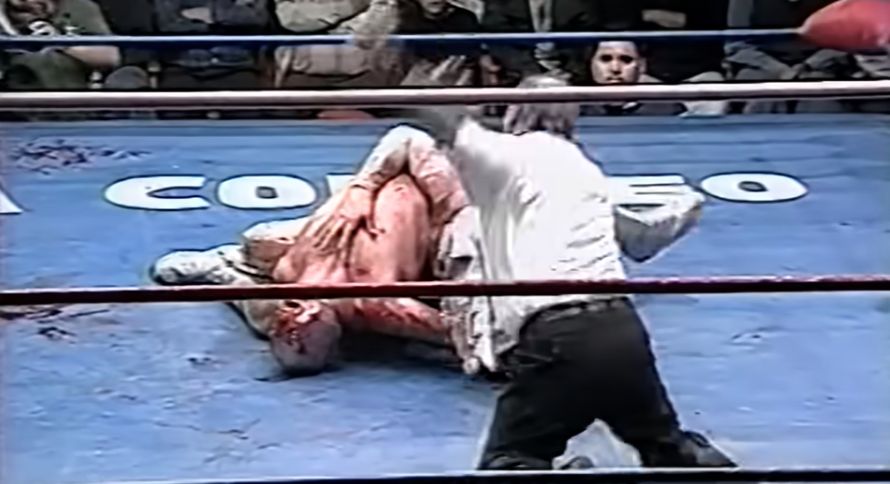

All of this, I should mention, takes place in the first nine minutes of the match, at which point Santito goes for another camel clutch, this one for the decisive win, only for La Parka to fight it off. His reward for such tenacity is a tope suicida that sends him flying into the second row. With victory firmly in his grasp, Santito throws Parka back into the ring, goes to the top, and attempts another tope, only for Parka to move and put the boots to him. I fucking love La Parka’s stomps, man. They’re vile and frenetic, the act of a man with bloodlust in his heart, and the fans immediately take to booing him despite his being on the receiving end of a one-sided and at times decidedly unfair beatdown. They want to see him punished, and he rejects that thoroughly, now throwing Santito back to them, first into the second row of one side of seats, then into the third row of another. He’s checking to see if he is bleeding the whole time and, finding that he is not, actually opens Santito up with a series of headbutts. He finds a bucket at ringside and lets loose on Santito’s head with it, and when he walks towards the camera you see that his silver-and-white bodysuit is now spattered with blood. Some of it is his, no doubt, but when he throws Santito back into the ring and the technico tries to steady himself against the ropes, you can tell that a lot of it is his opponents, his arms and torso now covered, his silver mask failing to contain the blood that’s pouring from his forehead. Santito’s mask is now torn, too, no doubt from the crowd brawling, but there’s a bright crimson pool oozing between the eyeholes, as if he’s been shot between them, blood pouring to the canvas before La Parka hangs him in the tree of woe.

It is here that I find myself at something of an impasse. What, realistically, am I, a gringa from the United States, supposed to say about this match that could possibly elucidate its charms, let alone its power over me? This is, I think, one of the issues that faces everyone who tries out wrestling criticism, whether their ambition is to chart wrestling as a business concern, to suggest which matches are worth trading tapes over, or to cover wrestling as an artistic medium. When I write about music at my dayjob, I often find myself writing, then deleting, a sentence about a moment of the song that “transfigures” a track that I like, not in the Christlike sense since most of the musicians I write about actively recoil at the idea of themselves as some kind of hero, but in the sense that whatever they’ve done — adding a blush of slide guitar here, backing away from the mic and letting their voice howl out on a chorus, leaving in the creak of a studio chair at the end of a take — has ascended to a higher, more difficult to describe plane than where I usually find myself with music. Sometimes it takes a lot of careful, active listening to find those moments, interviews with the artist, deep dives into past work, because the process of writing, recording, and releasing music doesn’t hold many secrets — it’s the way the ear and the heart respond to it that is the great mystery.

In wrestling, it’s almost the opposite. I know why my heart beats faster when a wrestler starts gushing blood — that’s a real man, that’s (usually) real blood, and the ticking clock nature of an athlete bleeding when combined with the artistic difficulty of holding something as physically and mentally taxing as a wrestling match together while bleeding out is a peculiar kind of magic, something that feels unique to the great sport of professional wrestling. But just the same, I’ve seen many wrestlers bleed in great quantity, and I don’t necessarily subscribe to the notion that most matches like this, if not all of them, have their places in history altered by the presence or absence of plasma on the mat. Does blood alone transfigure a match, transfix the eye? No. But when La Parka takes a bleeding Santito over to the ringside seats with white backing to throw him into them, and when the impact causes Santito’s blood to spatter against them as if the meat man from Hellraiser had sat there and scrawled “I am in Hell, help me” on them? Well, yes, at that point the blood matters, where I can tell you, as a fan and as a critic, that whatever this match was before El Hijo Del Santo started bleeding, it’s something else now, something you’d be a damn fool idiot (squeamishness aside) to not experience for yourself if you haven’t already.

It’s one of those bladejobs that immediately crystalizes the purpose of the match and its stakes, like a combination of Guerrero/JBL and Austin/Hart in that it renders Santito as the most sympathetic person in the building (if not the world) while drawing a line of demarcation around him as the hero and La Parka as the villain, which is useful given how close to the line Santito was riding in the first fall. It makes La Parka’s injuries feel small by comparison, a stroke of luck more than anything, an acceptable loss in the total and complete route of this legend and everything he stands for. The cameramen and the editor lose focus of La Parka’s conquest of Santito to show shots of the pools of blood on the canvas, and who could blame them? Nobody could survive this onslaught, and Santito does not, losing the second fall to a top rope rana.

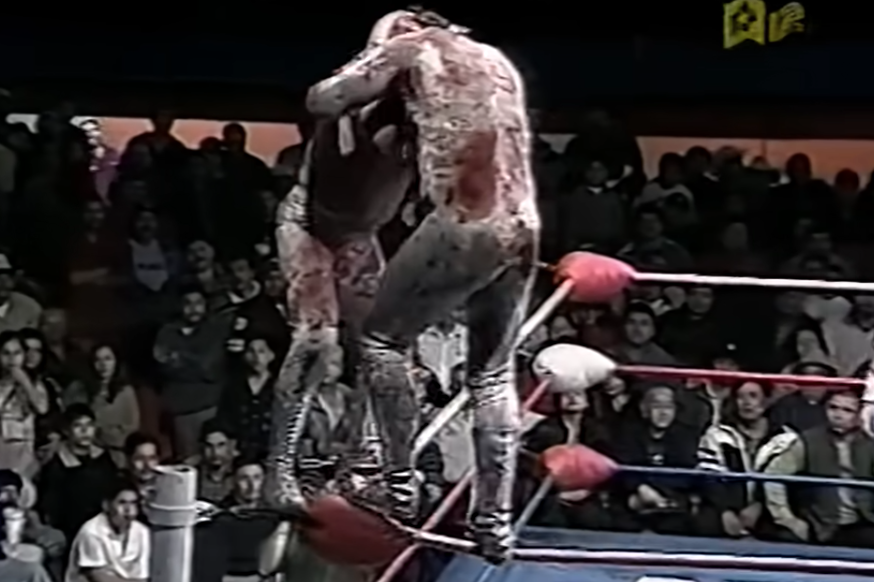

Things look bleak for Santito while he’s on the canvas, picking at his mask to keep it from drying to his face as his blood coagulates. He’s fortunate, in a sense, that La Parka isn’t satisfied with winning, choosing instead to keep the beating up at ringside. There’s a kid out there holding balloons, slack-jawed as he gazes at the carnage, which only relents when the chant of “SANTO! SANTO!” snaps him out of his stupor in time to avoid a rushing La Parka. He’s desperate to end things and shifts from his opening all-out assault to one where any move — a tope through the corner ropes that sends Parka barreling away from the ring, a surprise rana — could seal it, by countout or pinfall, whatever it takes. When La Parka hits Santito with a tope, the move has a way of reminding you of how much this match has taken out of him, too, with Parka on the floor getting fanned off by a towel as Santito reclines in a ringside seat. Parka gets back into the ring first, turning his back to Santito, convinced of his victory. Meanwhile, a fan gets close to Santito, clapping for him as if his support alone can shift the balance of the match — you lose Santito’s resulting charge to the ring to take Parka down and trap him in a submission for the sake of showing Parka crowing about the victory he hasn’t earned yet, which is the right call for the television audience, but ahh, man, what a spectacular little moment that transition is, how important the voice of the fans — be they one or be they 10,000 — is to the flow of a match.

Parka refuses to quit, both to it and the camel clutch that lost him the first fall, but he can’t win with his reprise of the surfboard, either, making the critical error of transitioning it to a pin too close to the ropes. The resulting exchange of nearfalls — Santito’s being on another plancha to the floor, La Parka’s on roll-ups — are a matter of literal inches, two men who have found themselves, beyond time, beyond pain and exhaustion, as the other’s equal, which neither will stand for. Ultimately neither man has much of a hand in the finish, as Santito bumps the rudo referee, leaving the technico one free to count the pinfall after an ecstatic fowl kick (this being a no-holds-barred super libre match), but the rudo recovers in time to counter the third stroke of the pinfall with an armdrag, counting a false pinfall before awarding the match to La Parka, who then gets a beatdown from the crew Santito sent to the back earlier in the match

It’s a disappointing finish to a sensational match, which once again leaves me at something of an impasse as a critic. If it’s possible for blood to transfigure a match, can something like what happens at the end un-transfigure it? This is something I’ve been finding myself against in projects like the WCW MONDAY NITRO MASTERLIST, where on a routine basis you’ll get three, five, sometimes as much as 12 minutes of incredible, poignant professional wrestling that is wiped off the board by what happens in the final 30-seconds. Much like in WCW, where the promised payoffs for these spoiled finishes never happened, La Parka and El Hijo Del Santo are not destined for an apuestas, eternally finding an out from the promise of mutually-assured destruction, as if the hate that undergirds this match does in fact have a limit.

The answer, for me, is “well, kinda.” As much as the moves made to protect La Parka’s image at all cost hurt the finish, there’s 25 minutes of unparalleled professional wrestling here to admire otherwise, wrestling of such mud-and-blood passion and conviction that you can almost excuse the referees for openly interjecting on the behalf of their favorite. The third fall does an excellent job of arguing, before any of that, that there are no winners between El Hijo Del Santo and La Parka, that the scales measuring them are so close to balancing out that they would, of their own accord, fight forever, if not to their last breath, that tonight in Monterrey they are the closest thing the world has ever seen to angels and demons, to the eternal struggle between them. It it has to end, and it must, there’s something real, something outrageous, in a human impulse like petty greed or favoritism being what does it. That, too, is some professional wrestling-ass professional wrestling, whether you want to admit it or not.

Rating: **** & ¾