Terry Funk and Ric Flair Sweat, Bleed, and Pay the Price at the Bash

Few wrestlers have had years as good as the ones Ric Flair and Terry Funk had in 1989. Their first clash is lightning in a bottle.

Ric Flair is not an easy man to like. Everything about him — the blond coif, the sequined robe, the way he knows exactly how much everything he wears costs, the women he brags about sleeping with, the food he says he eats, the way he pioneered travel via private jet as a vector by which one may come to dislike a celebrity — is tailored, like one of his Armani suits, to flatter him and infuriate fans. His genius as a heel was to turn himself into a site of class struggle, which is much more difficult to do than the proliferation of rich guy pro wrestlers before and after him would suggest — look at most guys who’ve walked that aisle, even wrestlers who legitimately do come from money, and there’s too much character in their character to make it work, a role that’s been assigned to them rather than one that they’ve earned.

The secret to Flair’s success is that he earned it, that he is, in some ways, a class traitor. Born Fred Phillips, Richard Fliehr was born a victim of notorious child trafficker Georgia Tann, an infant stolen from his mother right after his birth — in his autobiography, Flair posits that his birth mother, like many who fell for Tann’s scam, was likely told he was stillborn and given a set of papers to sign while under sedation. They were presented as a death certificate but were instead adoption papers. Baby in hand, Tann then worked to essentially sell them to their adoptive parents — The Knoxville Focus notes that it cost $7 to adopt a child in the state of Tennessee, but she was able to command as much as $5,000 for one arranged by the Tennessee Children's Home Society.

Unlike many who found themselves there, Flair got lucky — he was born on February 25 and was adopted on March 18, hand delivered to his parents in Detroit, where his father was finishing his residency as an OBGYN. They moved to Minnesota, where his mother became a columnist for the Star Tribune. He had a good childhood and loved his parents, but he struggled academically and gravitated towards athletics, finding himself particularly enamored with the exploits of the wrestlers he saw on TV. To become a wrestler when Ric Flair became a wrestler, you really had to earn it. He trained under Verne Gagne in the freezing cold Minneapolis winter with Greg Gagne, Jim Brunzel, Ken Patera, and The Iron Sheik. He debuted a year later for the AWA. He went to Japan for the first time in 1973, left Gagne for Jim Crockett in 1974, and in 1975, when he was just 26, he broke his back in a plane crash in Wilmington, North Carolina and was told that he would have to quit wrestling. He was back in the ring within three months. In 1981 he became the NWA World Heavyweight Championship.

He earned that championship and his place in wrestling every step of the way, and the bitter pill that fans had to swallow was that to Flair this was no miracle, no inspirational story, just a ticket to fame and fortune and power, a ticket he clung to like there was nothing else in the world worth living for. You wanted, badly, for someone to beat him and take the strap and the money that came with it, thrilled to the exploits of men like Dusty Rhodes, Ricky Steamboat, Ricky Morton, and other scions of middle America as they chased him across the globe, and yet some of the best moments of his career, like this, came when he was playing against type.

What makes Flair such an effective babyface is that fans of professional wrestling, until relatively recently, had long institutional memories. Watching Flair brag about the line around Space Mountain or bloody up some pretty-boy ahead of a title defense, you knew that Flair had scrapped his way to the top of the mountain, that he had literally emerged from a plane wreck that claimed the career of Johnny Valentine in doing so, and that in his heart he was a competitor first and foremost. If you have a fanbase with a long memory, it’s actually not hard to turn Ric Flair into a good guy: you just find a bigger bastard. Harley Race putting out a bounty on his head. Vader perfecting the powerbomb finisher and threatening to use it to break Flair’s back permanently. Terry Funk, middle-aged and crazy, spurned by Flair as being too-long removed from wrestling to reasonably expect a shot at the NWA Championship. A guy like that might piledrive you on a table. In 1989, a piledriver on a table might break your neck. And if you’re Ric Flair, a man who once slipped death and recovered from a broken back in three months for the sake of pursuing a wrestling championship, you might take that as a personal offence and a professional challenge.

As for Terry Funk, where do you begin? For most in the post WWE Video Library era, I suspect it’s with the Clash of the Champions “I Quit” match, in which Funk does the deed, admits his faults, and shakes Flair’s hand. Snatches of violence fill themselves in along the way — the piledriver on the table, the plastic bag over Flair’s head, the way he brutalizes a young Eddy Guerrero, his swift ascent up the Top 10 ranks — along with the music of his promos, the bitter, sour poetry of a man who above all else is afraid to reckon with the way he has spent his life. An outlaw and a drifter by nature, Terry Funk returns to the NWA in 1989 as a special guest judge for the final match of the 1989 Flair/Steamboat trilogy. He’d won the NWA Championship in 1975, defended it for 14 months, retired dramatically in 1983 but did not take his first full year away from the ring until 1988, the year he filmed Road House.

A career in Hollywood, which Flair accused Funk of being too interested in to be a contender in 1989, was not an impossibility — he was the villain and stunt coordinator for Sylvester Stallone’s post-Rocky passion project Paradise Alley, suggested Hulk Hogan for the role of Thunderlips in Rocky III, and had, by 1989, a list of credits that suited his character actor’s face and voice: a recurring role in the failed TV western Wildside, a part as a heavy in Over the Top, a TV movie called Timestalkers where he shares a billing with John Ratzenberger, Klaus Kinski, and Star Trek Voyager’s Tim Russ, but Terrence Dee Funk was a goddamn wrestler, and in picking this fight with Ric Flair, that’s how he was choosing to go down in history.

It’d be romantic if Funk’s motivations weren’t purely selfish. There are few heels as unlikable as the Terry Funk who ambles down to the ring to Ennio Morricone’s “Man with a Harmonica,” couching his actions in the notion of honor for the Funk family, for his father’s memory, conjuring up his ghost over and over again in promos as if his daddy might join in on spitting on the Nature Boy. He famously spoke of his beautiful dream, that his dad Dory Sr. was somehow on the porch at the Double Cross Ranch in Amarillo, sharing the father-son moment of laughing at Ric Flair’s expense. For someone so bent on ensuring the Funk name would live forever in the world of wrestling (which it would have had the Funk line stopped at Dory Sr.), he was doing his best to drag it through the mud.

All of this is brought to bear for the first time at the 1989 edition of the Great American Bash, “Glory Days,” Terry Funk desperately trying not to become the hollowed-out old-timer at the Legion Hall in the Springsteen song the show borrowed its name from. He’s a dangerous man, but so is Ric Flair. The question he has to ask himself is whether or not he’s done enough to unseat Flair. It’s also the question on the mind of Gordon Solie — is the champion at 100%? “In my mind and in my heart I am 120%,” Flair says. “If I’m not, we’ll know in about an hour.”

This match does not go an hour. Despite the solemnity of Flair’s tone in his pre-match comments, this is not a solemn occasion. It is a fight for survival. Flair must survive Funk. Funk must survive the relentless onslaught of time. Cue the goddamn harmonica.

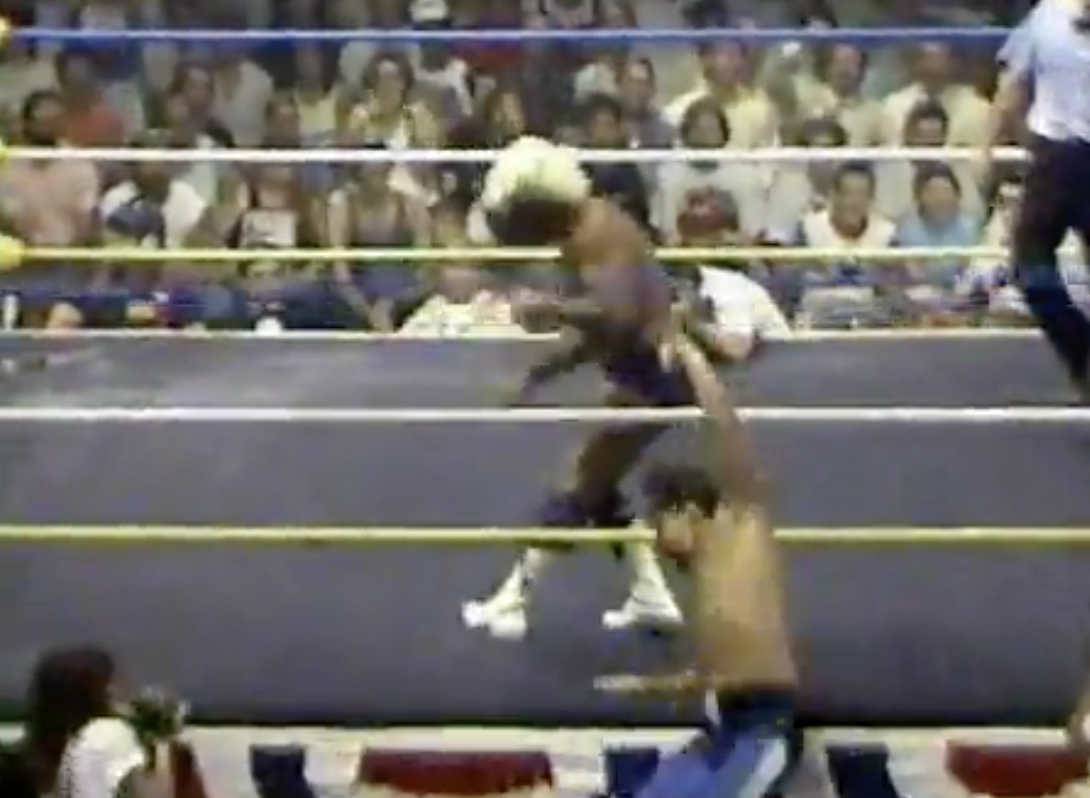

It must be noted that it is Terry Funk who blinks first. Middle aged and crazy, sure, but accompanying him to the ring this evening is Gary Hart, the leader of the J-Tex Corporation. It is Hart’s first night as Funk’s manager, the first time anyone calling the match can remember him having one, and if he was so confident in his ability to destroy Ric Flair, he wouldn’t need an insurance policy. Ric Flair, meanwhile, is Ric fucking Flair. Gold pyro raining from the ceiling, four women on his arms, the city of Baltimore, Maryland greeting him like a king returning victorious from war before he’s thrown a single chop. It is an atmosphere unlike most in wrestling history, and it only builds as Flair chases Funk down the aisle to assault him on the floor, punching and chopping and biting at the Funker before the bell rings.

Flair has beaten Funk to his own game, and in the early moments of the match his rage is palpable. He often throws tantrums at ringside, leering at and threatening fans, throwing chairs and pulling apart the barricades, and Flair lets him stew in that mood for awhile before coming after him again with a double axe-handle off the apron. The methodical, confident pace Flair usually wrestles at, the championship pace that’s structured around 30-60 minute exhibitions of skill and grace, has been replaced by the blood-and-bile brawler who comes out at the WTBS Studio in Atlanta, the dirtiest player in the game reborn in the righteous fire of vengeance.

That’s all well and good, but it’s a dangerous mindset for a defending champion. With Funk throwing chairs and making him wait, Flair takes issue with the referee, shoving him aside several times to put up his fists and challenge Funk to fight. It’s in this moment that you can see how the motivations of both men have changed: Terry Funk, having failed to put Ric Flair out of wrestling, wants to win his title, Ric Flair, having survived Terry Funk, wants to settle a score. Funk’s selling, a magnificent amalgam of spaghetti western death sequences and Tex Avery cartoon violence, gives Flair a taste of vengeance with every blow. A chop sends a shiver down his spine. A punch snaps him front to back as if commanded to do an about face. Another sends him into the ropes like a Rocky villain. A second chop sends him over the top rope and to the floor. The crowd goes “BOOM! BOOM! BOOM!” with every blow Flair lands, a key affectation of an 80s NWA crowed, adding to the impact.

It’s not enough to keep Funk down. When Flair hits the floor with another diving strike from the apron, he responds with a punch to the gut, then sends Flair head first into the ring post. While Jim Ross and Bob Caudle espouse the scientific wrestling prowess of both men, Funk hits Flair with some gnarly boots to the face, simple “I have the high ground” tactics that knock Flair out of his game. After slapping Flair a few times, he demonstrates that prowess, bringing Flair into the ring with a suplex and going for the cover for an immediate two count. He fails to lift Flair for a second suplex, but it doesn’t matter: his target is Flair’s neck, and lifting a man up a third of the way towards a suplex from a front facelock is going to mess with his neck just as well as the move itself. You can see how effective this attack is when Flair tries to fire back at Funk with a headbutt and recoils as if it’s damaged him more than the challenger, when he tries to suplex Funk, this time out of the ring, but doesn’t have the strength to complete the move and tumbles to the floor along with him. When the two of them get up from this fall and start brawling, referee Tommy Young, already letting a lot of the rules slide due to the intensity of this rivalry, breaks his “back in the ring” spiel by saying “they’re trying to kill each other.” At this point it’s only a minor exaggeration.

Back in the ring, Funk goes for the piledriver, the move everyone is worried about, but he hasn’t done enough to Flair, who backdrops Funk over the ropes. It’s a nasty spill to the outside and, along with Funk’s earlier ringpost-attack, questionably legal according to the NWA rulebook. More importantly, it makes Funk’s neck a target, which Flair does not hesitate to go after. He does a couple of those neck cranks that you see in action movies where one guy breaks another guy’s neck and drops his trademark knee across Funk’s back. Funk’s facial expressions, the way he uses his arms, the way he oversells the knee drop by humping the mat, then does a Three Stooges circular scoot around the ring to sell a piledriver, sends the crowd into a rapture. Funk dead sells a second, nastier piledriver, tries to get up, spills out of the ring, then tries to escape Flair, crawling up the aisle on his hands and knees.

There are, I suspect, some people who don’t really dig the over-the-top aspect of Funk’s selling. Or maybe they say that they do but criticize it when someone who isn’t Terry Funk does something like it. All I can say to this kind of person is that they’re fucking wrong. Wrestling, particularly this kind of wrestling, is about emotional release. There are hundreds of schools of thought on how to best achieve this, many of them valid, but Terry Funk is the greatest wrestler of all time, and his take on wrestling, gritty and low-down as it may be, does not strictly adhere to what one might call realism. There are over 10,000 people in the arena, over 100,000 people at home, and most importantly there is one man in the ring aching to see Terry Funk pay for his sins, to be shown as a sniveling coward, and his every twitch, gesticulation, and pratfall delivers on the promise of the show. By the halfway point of the match, it is over. You know this match is Flair’s for the winning, then he locks in the Figure Four. Enter Gary Hart, distracting the referee while throwing a branding iron Funk’s way.

There are several moments prior to this where Flair or Funk could have chosen to start bleeding, but it’s great that they wait until this one, where Flair had the match snatched away from him, where Funk had no escape and revealed that he was, as Flair said months prior, no match for the champion in his prime. No longer on his hands and knees trying to crawl away, Funk works on opening up Flair’s wound more, closed-fist punches serving as the prelude to his own piledriver. Funk makes the tactical error of pinning Flair too close to the ropes, but the champion doesn’t have enough to get his arm or leg on one — Young notices that Flair’s foot is underneath the rope, through no action of Flair’s and stops the count.

With Flair bleeding and Funk kneeling on his neck, one wonders if Young is doing him any favors. Funk goes outside, rips the thin mat away from the floor of the Baltimore Arena, and goes to piledrive Flair on the concrete. Flair reverses it, back body dropping Funk onto the mat, but the challenger is up first, gets onto the apron, then desperately throws himself onto Flair, who sells as if Funk landed his full weight on his neck. This and a couple of neckbreakers renders the arena silent, but Funk is on another plane of reality at this point, demanding that Flair verbally submit to him, that he says “I quit,” while Gary Hart begs him to just take the pin.

It’s a logical request, but Terry Funk is an illogical man. He’s stubborn and hateful, full of wounded pride, a dangerous fool who sees victory before him and decides that it isn’t enough. Bob Caudle kind of casually regards Funk’s stratagem as a tactical error — Ric Flair will never quit so long as he breathes, he claims — but Flair is already bleeding heavily in a promotion where blood loss can result in a title change, has relentlessly worked over a broken neck in a promotion where referee stoppage or a knockout can result in a title change, and he sees no way out for a cornered Ric Flair. Whatever he’s said in the lead-in to this match, he honestly believes that Ric Flair humiliated him when he asked for a title shot, and this is his payback. Is it a mistake to go for a verbal submission? Sure, but it’s not nearly as damning an error as bringing the branding iron back into play, letting Flair grab it away, and taking it to the dome.

Funk’s blood energizes Flair — he has weathered the storm and is once again in a position where he is his own worst enemy. While Flair punches away at Funk in the corner, Tommy Young yells “control yourself!” at the champion in an effort to create some space, foreshadowing a failed attempt at a killing knee lift in the corner. Funk locks in the spinning toe hold, his championship winning hold, but Flair’s a master of the game and works to reverse it into the Figure Four. Funk turns that into a cradle, Flair reverses it, and that’s three. A dead heat that comes down to a leverage move, a classic piece of professional wrestling that proves Flair to be the better wrestler while keeping the door open for Terry Funk, who was just barely beaten.

The Great Muta immediately busts that door down, pelting it to the ring as soon as the bell sounds to continue wailing on Flair. Sting rescues the champion from the hands of Funk and Muta, providing the new top heel stable of the J-Tex Corporation, a fusion of wrestling’s past in Funk and its future in Muta, with its babyface mirror. It’s a wild brawl, with head of security Doug Dillenger taking his rare lick, Sting and Flair ultimately clearing the ring. “This one is far from over,” Jim Ross declares. He’s right, but like many things in the careers of both Ric Flair and Terry Funk, were this the end of their issue, it’d be on an impossibly high note, one of the greatest professional wrestling matches of all time.

RATING: *****