Shawn Michaels and The Undertaker Battle for the Soul of WWE

And it turns out that the soul of wrestling, like wit, is brevity.

One of the nice things about leaving Twitter is that it’s been a moment since a wrestling fan accused me of posting engagement bait. I understand the impulse — there are people out there who post truly dumb bullshit about this great sport, for money or because they have a fetish for being yelled at, but I come by my unpopular opinions honestly, and one of my most unpopular opinions is that The Undertaker sucked. It may not surprise you, then, that I’ve never really been a fan of his pair of WrestleMania matches against Shawn Michaels.

A lot of that, I think, stems from my general distaste for the idea of WrestleMania itself, much of which, it turns out was built around the aura of The Undertaker’s undefeated streak and Shawn Michaels’ standing as Mr. WrestleMania. It’s fine — good, even — for a wrestling promotion to have signature events like WrestleMania: a big, easily accessible show that guarantees a huge gate and clears the deck of months worth of storylines for the sake of beginning a new cycle is arguably the greatest idea anybody in wrestling has ever had. The sour thing for WWE’s conception of the wrestling cosmos is that that idea was not WrestleMania, it was Starrcade, billed righteously and correctly by its co-creator Dusty Rhodes as “The Granddaddy of ‘em All” because it was just that, only WCW lost the handle on how special the concept was, whereas every WWF PPV pointed to the importance of WrestleMania, which had serialized numbers like the Super Bowl and often featured a main event of the WWF Champion vs. a guy who’d beaten the entire roster in the Royal Rumble.

WCW folded a whole six days before WrestleMania X7, WWF’s first WrestleMania held in a stadium since 1992, and from that moment until the heat death of the universe, WWE’s narrative is always going to be that WrestleMania is the peak of the artform, that every wrestler in the world should live and die by their dreams of either headlining it or stealing the show. When I checked in on WWE programming for the first time since last year’s WrestleMania, Seth Rollins was trying to use his being the fourth most important person in the dogshit main event of night one of WrestleMania 40 as proof of his superiority over CM Punk, who has zero WrestleMania main events to his name. Again, all well and good to brag about accolades and money — wrestlers standing on their wallets is a time-honored tradition — but when it happens in WWE it always ends up feeling like what we’re talking about isn’t wrestling, but shareholder value.

Short of maybe Triple H, few wrestlers in WWE history were more shareholder value-orientated than Shawn Michaels and The Undertaker, and I’m not sure anybody, even Cody Rhodes, is going to catch up to them. The last scions of WWE’s most marketable era, Triple H and The Undertaker were the main stars of Raw and SmackDown during the early brand split, presiding proudly over a period of declining business that must have made Shawn Michaels, the leader of the New WWF Generation, feel right at home when he returned from a what was thought to be a career-ending back injury, clean from drugs and redeemed in the eyes of the Lord.

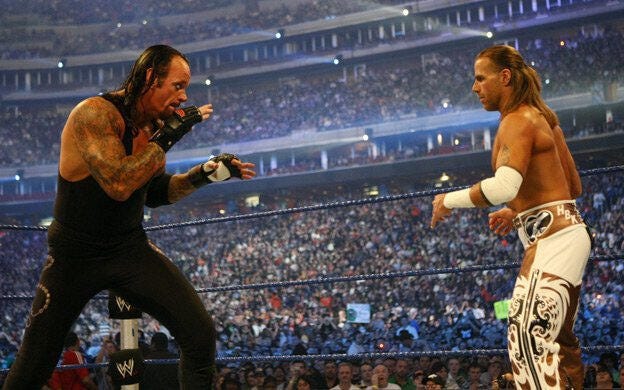

WWE’s main event in-ring style changed a lot during this era, partly due to Triple H’s fetishism of JCP-era NWA, and partly due to changing roster composition. I haven’t seen it all, but in my estimation two of the biggest beneficiaries of this change were Michaels, who could not and thankfully no longer had to run every match at the lightning pace of either his athletic or drugged-out peaks, and The Undertaker, who finally started having good-to-great matches with wrestlers who weren't Michaels or Bret Hart. One of the selling points of Michaels’ second WWE run was the spectacular quality of his WrestleMania matches (this is debatable, but has been marketed so well that it’s true to most people who care). One of the selling points of Undertaker’s WWE career was that he was undefeated at WrestleMania. Put those things together under the auspices of The 25th Anniversary of WrestleMania (really the 24th anniversary, but hey), and you have yourself something as on-paper compelling as The Megapowers Explode or The Ultimate Challenge or Rock vs. Austin at X7 — a huge match between beloved stars that was both a wrestling match and an ideological battleground.

My problems with the match, going into this rewatch, were two-fold. First, I fucking hate the question it poses. At this stage in their careers, both Undertaker and Michaels were being positioned as something of the WWE’s conscience. Again, shareholder value nonsense, but I guess they both had a claim to it, as running a kangaroo court for wrestlers backstage and aiding in the Montreal Screwjob is some Best For Business shit on the order of ratting out a wrestler’s union. No viewing of this match or its follow-up is going to resolve that. The second issue, though, is that I really love those Michaels/Undertaker matches from 1997-1998. Other than some tag team matches and a 1995 house show match, the two never really entered each other’s orbit until SummerSlam 1997, when Michaels was the guest referee for The Undertaker vs. Bret Hart, a match that would be the WWF’s best of the year, and maybe the decade, if it wasn’t for Hart/Austin at WrestleMania 13 or Michaels/Undertaker at In Your House: Badd Blood.

It’s Bret Hart who is the shit-stirrer there, ducking an enraged Michaels chairshot after spitting in his face, capitalizing when said chairshot hit the Undertaker. Michaels was a babyface at the time, returning from losing his smile and winning the tag titles with Steve Austin, and while Shawn’s heel turn was less shocking than Bret’s (Shawn was a preening egotist and no real hero even when he was a babyface, whereas Bret’s turn was predicated on the fans betraying him because he wasn’t cool anymore), it was hugely effective — he may not have meant to hit the Undertaker, but he didn’t exactly need a hard shove to become the founder of D-Generation X: it is heel Shawn Michaels cannon that he’s a coward who needs a heater, why not Hunter, Chyna, and Rick Rude?

Undertaker was a perfect foil, too, someone Michaels could run from and bump for, who, like too many WWF main eventers 1996-2001, was mad about getting screwed out of the title. If you want to be extremely gracious to Vince McMahon, look at what Michaels was doing with The Undertaker and compare it to what Bret Hart was saddled with in The Patriot, and you can almost make an argument that McMahon made the right call in letting Hart go in a career year where he made and ostensibly re-made the headliners of WrestleMania 14. The energy crackling from Michaels and Undertaker is palpable, real “future of this business” stuff, were it not for how short Shawn Michaels’ future in the WWF was.

It would be unfair to hold either issue, or even this match’s standing as the template for WWE epics going forward, against it, and I won’t, but “Undertaker/Michaels at WrestleMania 25 isn’t good” being my hot take, I needed to explain it before coming to my new conclusion, which is this: The Undertaker vs. Shawn Michaels from WrestleMania 25 is accidentally great.

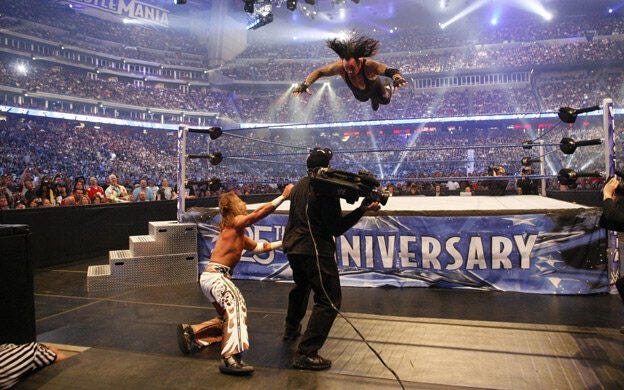

“Accidentally” may strike you as an odd word to use about a meticulously constructed epic, but the best moments of this match come at the expense of the plans of Michaels and Undertaker, most famously in the instance of Taker’s famous over the top rope dive, which Jimmy Snuka Jr., in cameraman garb, failed to be in position for. As designed, it’s a signature Undertaker spot that calls back to Michaels abusing the cameraman during Hell in a Cell ‘97, plenty spectacular but just a bit of ol’ HB-Shizzle playing the part of trickster on The Undertaker. As it plays out, holy shit. It happens right after Shawn Michaels eats shit on a moonsault to the floor, so Taker crashing and burning right after, going risk for risk and coming out the loser, brings out the wild-ass spectacle of their early encounters, turning the clock back to when both men would kill themselves for the sake of putting the other in the grave.

The other spot I freaked for here was the Tombstone Piledriver Taker delivers on Michaels as he’s skinning the cat after being thrown over the top rope. As planned, it’s Taker foiling a callback to a signature Michaels spot, his victory in the 1995 Royal Rumble specifically, an emphatic Tombstone that would have been a monster nearfall/future meme had all gone perfectly, but here Michaels’ head goes under the bottom rope and, to make the spot go, he basically has to hang himself for a few seconds and needs Undertaker to pull his ass back into the ring, rope by rope, instead of the intended clean motion. It looks painful. It seems like a struggle, and it is, not just between the two men in the ring.

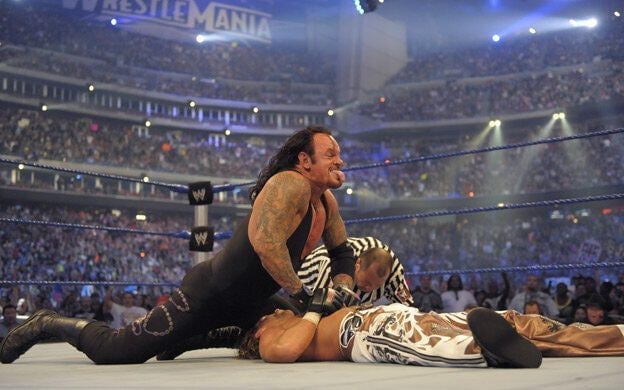

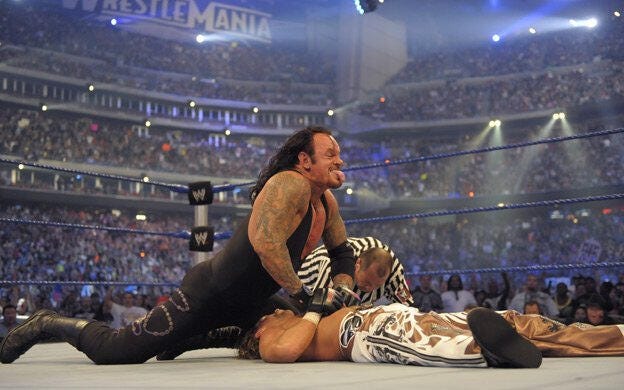

When Michaels loses this match, it kicks off the year-long denouement to his retirement at WrestleMania 26. How much Michaels had in the tank when he retired is immaterial, but in those two spots you can see time running out for both he and The Undertaker, who is saddled with the twin misfortunes of needing to close out the streak and chasing after a final match that would have been half as satisfying as this. A year beforehand Michaels had put Ric Flair out to pasture in one of the hammiest matches in history, and while a lot of that match’s Acting makes its way here, neither wrestler is fighting to demonstrate his love for his opponent, and The Undertaker is not as good of a wrestling actor as Flair or Michaels. Undertaker’s disbelief when Michaels kicks out of chokeslams, Last Rides, and Tombstones, goofy as it seems now that it’s been copied to death, feels like legitimate frustration, a big ol’ slab of aged meat sucking more and more wind as he finds himself in deeper and deeper water with a guy whose conditioning is beyond reproach.

Shawn Michaels’ stamina is, per usual, both a blessing and a curse. It’s been ages since I’ve seen his Iron Man match against Bret Hart, but a pattern that emerges in his career once he steps into the main event is that he tends to go long for the sake of it, sometimes as a hit job (gassing out his friend Kevin Nash early at WrestleMania XI and taking him 20), sometimes because he mistakes length for quality (your average HBK vs. Triple H match), especially when the occasion appears to call for a kind of classic grandeur. Against The Undertaker, without a gimmick providing external structure, that’s concerning: this is the longest straight singles match of his career, almost the longest period, and the things The Undertaker can do without a gimmick fit best into smaller packages, 15-20 minutes of aura and bombs.

In other words, there is a lot of padding in this match, and while the back half of strike and finisher exchanges clearly works for the crowd, it’s worth noting that this is the first good wrestling they’ve gotten all night besides a brief snippet of Chris Jericho vs. Ricky Steamboat, and it’s not like they’re going to be eating good with the double main event. 13 minutes pass before Michaels goes up for his missed moonsault, and there’s a good minute or so of “I’m going to call this match” playacting with the referee before Undertaker takes flight. If you’re a fan of “feeling out processes” then there’s plenty of that in store for you here, but I’m a fan of when the things that happen in the opening moments of a match matter to its conclusion, and nothing here really does — they’re wrestling to a point that neither man’s advantage over the other matters, home run swings only, so when Michaels gets unnecessarily fancy trying to feint out Taker or chooses to work on his leg, it’s in service to the clock and not the story.

It’s a bit of a shame, too, as some of Michaels’ best selling is in these opening moments, catching Taker’s fists for the first time in over a decade and really relishing being thrown into the corners by a big man. Taker’s still got a little explosiveness left, too, and his running attacks in particular have a lot of body to them. Michaels’ biggest ideas at this juncture are to play towards his legacy of great WrestleMania matches by applying dogshit versions of the Figure Four Leglock and the Crippler Crossface, both looking like moves he is applying and Taker is receiving for the first time, Chris Benoit looking up from hell and having a good laugh. On stream Joseph and I kinda busted on the sequence that ends with Shawn in the gogoplata, Taker full-on flat back bumping on a feinted Sweet Chin Music that Jim Ross says hit low, but watching it through a few times I think it’s actually a pretty successful spot that nobody really had context for at the time, besides Michaels trying to trick Taker being the one theme that carries through from beginning to end. After slipping a chokeslam, Michaels doesn’t have the space necessary to hit the Sweet Chin Music in a meaningful way, but him going for it will draw a reaction from Taker, who can’t duck (the standard counter) because he’s too close, so instead he goes to his back. He’s not proficient enough in MMA to call this anything resembling spider guard, but he does watch as Shawn goes back to the well on the Figure Four, doing the full Flair turn-and-wrench, which Taker is intimately familiar with, going back to 1991. He’s waiting for Shawn to turn back, outmaneuvering him on the chessboard, and while the Hell’s Gate always looks like ass, you don’t need to do it perfectly to choke a guy out — it’s the first time either man is seriously imperiled by the other, and then they turn up the gas — moonsault, Taker dive, the sort of moments that transfigure wrestling matches to legend.

Which is what this match has become, to many, and if that’s the case for you, that’s cool. It is to both wrestlers’ credit that the match doesn’t fall apart after that dive — even with the built-in time for Taker to get back up, stretched out by Michaels and the referee as much as possible before he starts counting, there are no guarantees. Michaels praying for a countout win in the corner while the referee slowly counts feels like a slight betrayal of his character, but the fans buy into it, booing because the match they came to see might be over, cheering when, miracle of miracles, Taker begins crawling back to the ring — in a way he’s living out the surreal stretch of time between Mick Foley tumbling off Hell in a Cell and his climbing back up, awe giving way to disappointment giving way to anticipation of what’s to come next. And for however goofy it may be in character for Michaels to pray for a cheap win, who knows if he’ll have another moment quite as ripe as that to win, even if it’s flukier than the ones in 1997 and 1998.

The second half of the match is, in some ways, a career performance from Undertaker. He’s not especially known for his selling, even after his run as the American Badass broadened his palette a bit, so this match stands as probably his very best effort on that front. What works its way into the rest of his career are his disbelieving facials, but for me it’s how unique and strange it is to see him struggling against the ropes so often, eyes rolling back like a boxer who took one on the chin instead of an undead zombie carpenter. The Undertaker has one of the best chokeslams in wrestling history, and the one he hits Michaels with when he gets back in the ring is the best one he’s ever done. He dead sells a Sweet Chin Music, no lights on upstairs, and gets a last split-second kickout that’d tear down an Attitude Era venue, blind and sudden.

But those are early peaks in a 14-minute second act that revolves entirely around the Sweet Chin Music and The Undertaker’s various finishing moves, at once two men making up for a decade’s worth of lost time by throwing out as many variations on counters to both as they can and a well that’s not as deep as it seems. WWE has had a lot of Five Moves of Doom wrestlers in its history — it’s almost a prerequisite for an ace — but post-injury Michaels, whatever you think of him, did not have the same second gear that he did in the 90s, and he finds himself repeating ideas. That is one of the motifs of the match — he gets caught repeating the figure four, gets caught repeating the moonsault, etc. — but it’s his use of the Sweet Chin Music, both counters to it and kickouts from it, that feel increasingly ineffective, especially when The Undertaker is doing desperation top rope elbow drops. If the match ended on the skin-the-cat Tombstone, that wouldn’t be a problem — there is, from that moment, no more story to tell. But Shawn leads Taker to tell that story twice — he kicks out from a knockout Sweet Chin Music, he catches Shawn out of a signature HBK spot and lands a Tombstone — and that’s where the years where this match entering WWE curriculum eats away at it a little, not only because most wrestlers Terry Taylor has forced to memorize this match don’t have finishers half as well protected as Taker or HBK’s, but because it’s not even that good: after 30 minutes of wrestling and one near death experience, the finish of this match is obvious enough that there’s a fan in the background emphatically signalling for the Tombstone while HBK is climbing the ropes.

How many stars is going on seven minutes too long worth? I think for me to really know, Snuka would have had to have caught The Undertaker. As repetitive and ponderous and awkward as it often is, as much as its bones are showing, it is one of a handful of matches where The Undertaker is actually presented as the company-defining legend that even a loose reading of his in-ring career riddles dozens of holes in, and, despite the incongruity of good babyface descended from heaven Shawn Michaels praying for a countout win, is also the best read on his character from 2002-2010: a great wrestler who got a second chance at his life and career, capable of victory but far more potent when he comes up short. A year later, building to the retirement match, Michaels will claim that he was close to beating The Undertaker, that were it not for his mistake of going for a moonsault, he would have won. It’s a good line for him while he’s gathering his courage on the eve of what wound up being his second-to-last match, but it’s not true: The Undertaker had his ass in 1997 and 1998 but for DX and Kane, and barring the interjection of God, he had his ass at WrestleMania 25. God didn’t show up for Shawn at Backlash 2006, and he didn’t answer Shawn’s prayers here, unless his answer was to teach Shawn some humility, in which case the extra seven minutes should be worth a star. But I don’t believe in the God of Shawn Michaels, and I enjoyed this match much more than I thought I would, so it doesn’t.

Rating: **** & 1/4