In South Africa, Bret Hart and Steve Austin Realize Their Potential Together

Before their famous Survivor Series 1996 clash, Bret Hart and Steve Austin find out that they're perfectly suited to hate each other in South Africa.

A couple of weeks ago, Kazuchika Okada and Kenny Omega had their first singles match since 2018, an occasion so important that All Elite Wrestling billed it Omega vs. Okada V. It was, by my reckoning, the 20th time the pair found each other in the opposing corner. I know that what’s important, at least to history’s reckoning of the pair, is the five singles matches they’ve had, but I am and have always been a sucker for what comes before the bell rings on a historically significant match: the tease of a WrestleMania main event during the Royal Rumble, the endless slew of six-man tags before WrestleKingdom, a match that only makes it to tape because a fan snuck a camcorder into a show that took place years before a famous rivalry. However delicious the fantasy of two wrestlers locking eyes for the first time and making history is, the truth is that few matches that shake the foundations of professional wrestling happen in that kind of vacuum.

Nobody would say that of Bret Hart and Steve Austin’s WrestleMania 13 masterpiece, but what about their equally great clash at Survivor Series 1996? Billed by the World Wrestling Federation as Hart’s return to action after a self-imposed hiatus from the ring following his loss to Shawn Michaels at WrestleMania XII, the match was neither his first since March nor his first against Steve Austin. Like when Randy Savage was forced to retire but worked overseas dates to “keep contractual obligations,” Hart wrestled three tours for the WWF while he was off TV. In April, he went to Germany. In May, he was on the Kuwait Cup shows. In September, he worked the South Africa loop. On each and every one of those tours, he wrestled Steve Austin.

Survivor Series 1966 was their seventh match together. This was their sixth.

At the risk of sounding dull, the match is appropriate to its time, place, and the station of Hart and Austin — one man the featured star anchoring the tour, the other just really coming into his own in his still-new “Stone Cold” persona. They have no beef, just the will to compete, and unlike their later SummerSlam ‘96 encounter, this one isn’t designed to lead into something else. There’s no title on the line, no territorial turf for one of them to stand on, but the vibe before the bell rings is reminiscent of when a travelling NWA champion would visit a territory, put the title on the line against a popular local wrestler who was verging on a breakout, and work 15-20 minutes to help nudge them up the ladder. Only it’s not a local, it’s Stone Cold Steve Austin.

It falls to Austin to set the tone for this, as Hart has yet to become unmoored from his sense of justice — he’s a guy who made a commitment to be here, a guy who might not be in as good of ring shape as his opponent, a guy who might not even be in the WWF all that much longer, if you could imagine such a thing. Austin could seek to exploit that, but the early days of the Stone Cold character were marked by insecurity, of his perception that he wasn’t appreciated as much as he should be by the fans or fellow wrestlers or his employer, so instead of rushing in to attack Hart, he argues with the fans. He isn’t afraid of Hart, but he is playing a game with him, hesitating before ultimately choosing to try to outwrestle Hart, which takes one’s mind off of the potential for any ring rust on Hart, evening the playing field and allowing the Hitman to work at a more measured pace, relying on his cleverness as opposed to any frenzied violence, at least at first.

They don’t really build to one, either. They don’t build to anything, in fact, because it’s an exhibition. On the surface, that exhibition is of Hart, unquestionably the biggest name on a South African tour that also had Owen, Bulldog, and Yokozuna rounding out the cards — he’s the name they built the tour around and scored a TV special from, most likely. But if you look at Steve Austin’s 1996, even including his King of the Ring 1996 victory, two things stick out: Vince McMahon had absolutely no fucking clue what to do with him, and his two most important wrestlers loved working him. He was constantly working house show and dark match main events against Shawn Michaels and Bret Hart that year, and while he lost every single match on every loop where either match was featured, they did more to prep him for his ascent to the top of the card than his house show programs against Bob Holly or Duke Drose, and give us a better indication of what he would have looked like as a top heel than his (pretty damn good) program against Savio Vega.

The Hart matches I’ve seen in this mode are better, not in a “Bret is better than Shawn” sense, but because Bret’s much better at hiding that he’s not going full-tilt in a B or C-town than Shawn was, particularly in 1996 when Shawn’s whole thing was how he could only go full-tilt. Hart’s thing is precision and control, and if you’re a good heel you can convey a lot when you’re on the wrong end of a wristlock. Austin is a great heel, and he’s in front of a crowd that wants to boo him, to gloat as he suffers, and he gives them every opportunity. Austin sells the hell out of Hart’s basic wristlocks and armbars, intentionally goes for odd set-ups to his own basic moves to give Hart a counter (his chinlock setup is particularly weird, and Hart and Michaels have the same counter for it), all to heighten the perception of Hart as an elite-tier technical wrestler without having to go too hard on the last night of an overseas tour.

Again, I feel like I’m underselling this a bit. Yeah, it’s a house show match, all but non-canon, but the early Hart/Austin dynamic is on full display here, even without a build. Steve Austin’s “Ringmaster” persona is long dead, but from the end of the Hollywood Blondes in World Championship Wrestling to the moment he was baptized in blood at WrestleMania 13, his character was that of a man who was convinced that his gifts as a wrestler were being overlooked, that he was the best wrestler in the world but didn’t have the same machine behind him that made great wrestlers like Ric Flair, Ricky Steamboat, and Bret Hart household names.

He was right, of course, but the magic of Austin’s various heel personas before 1997 was that he had come up in Dallas and Tennessee, where a heel’s ability to give the babyface shine really mattered. Until the Stone Cold Stunner became the most over move in the history of professional wrestling, Austin was an utterly selfless performer, someone who immediately got the gist of being a heel and only got better. His wrestling debut was in 1989. This match takes place just days before his seventh anniversary as a professional wrestler. He was a prodigy and had a lot of meaningful time across the ring from Bill Dundee, Chris Adams, Barry Windham, Sting, Ricky Steamboat, Arn Anderson, Ric Flair, Sting, Dustin Rhodes, and others — his style was entirely different from just about anything else in the WWF at the time.

It’s fascinating to watch that in a setting where the stakes aren’t quite as high — you wouldn’t put this on the same pedestal as Hart/Austin at Survivor Series or Mankind/Michaels from Mind Games, but you can see Hart and Austin raising the bar for what the WWF’s in-ring product could look like and accomplish in real time here, hold for hold and strike for strike. It’s not the moment where you realize that Austin is the guy, that won’t be for another couple of months, but it is a star performance from a wrestler who has known his own worth for years and was waiting for the right opponent, the right time to fully realize it. There are hints that Bret Hart is the right opponent — his frustration with Austin’s stooging early is great — but by the time Austin takes this one outside and tries to piledrive Hart on the concrete, they aren’t hinting anymore: there’s something smoldering beneath the surface of the match, something to each man that pisses the other off. Watch Austin’s facials when he’s in control, look to Bret’s plancha and high-speed bailout through the middle ropes — this shit means something to them.

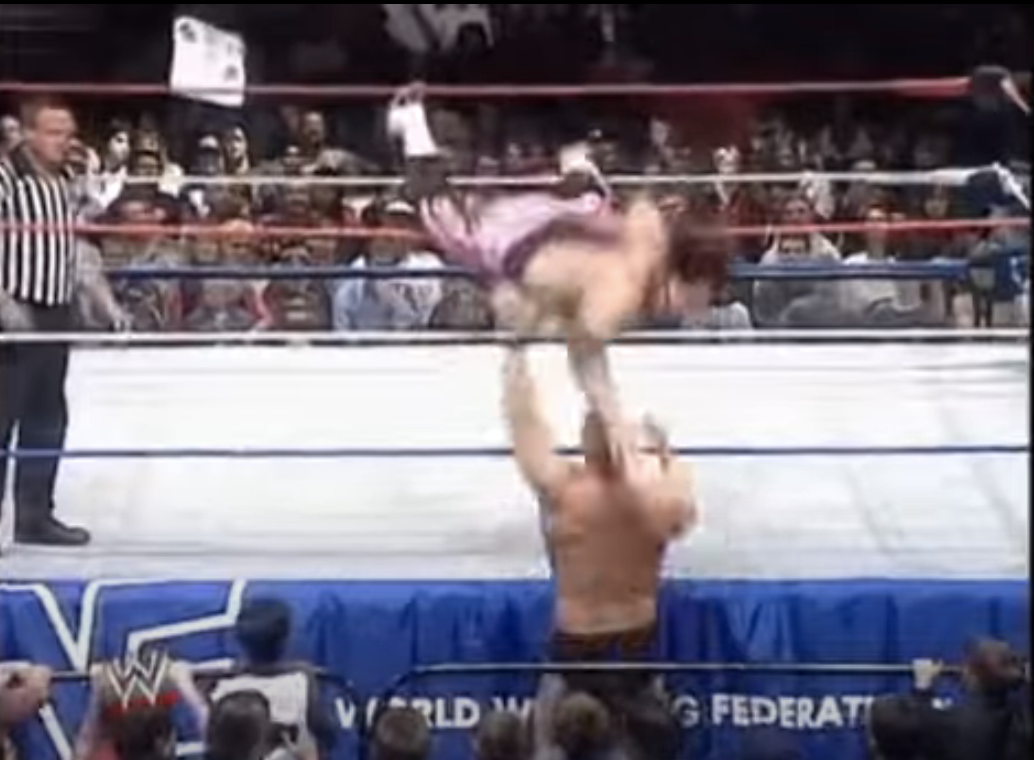

The finish is incredible, a lot of little adjustments to Hart’s routine that make each blow feel decisive. Austin immediately goes for the cover on a Bret turnbuckle bump, then goes for a superplex, but is thrown off. Already on the top rope, Bret goes for the ultra-rare top rope elbow drop and lands it, which Owen Hart, making light of Hart-family trademarks being his all night, points to as being out of character. He also fails to go for a pinfall, which is a mistake, as he gets thumbed in the eye. But he’s the good guy here, still, and will be until the city of Chicago decides it doesn’t want a hero anymore, so Austin really belabors the Stone Cold Stunner and ends up getting countered into a signature corner-assisted pin by the Hitman, the sort of thing he usually only breaks out when he’s winning a championship at WrestleMania or The SummerSlam. He has beaten Steve Austin, clean as a whistle, but every tell you look for in a Bret Hart match is here: he considers Stone Cold an equal. In just a few months, the rest of the world will see what South Africa saw.

Rating: **** & 1/4

After years of threatening to do so, I am finally following through on a longform exploration of Toru Yano's G1 Climax matches, over at BRUISER. The first four matches are up now: Mox (2019), Tanahashi (2007), Nakamura (2007), and Styles (2015). All heat, baby!