GAEA Kicks Off With a Tag Team Brawl That Rivals the Very Best in Wrestling History

All you need to do to make wrestling good is to competently shoot and edit some of the greatest wrestlers of all time. Blood helps. So does the finish. But it's easy!

This is what you call a statement. The first main event of the first GAEA show, and right out of the gate, Chigusa Nagayo’s conception of professional wrestling and her place in it is as clear and marvelous to behold as Atsushi Onita’s. I won’t pretend to know the ins and outs of Nagayo’s career — I’m familiar with the Crush Gals, but not majorly so, my interest in joshi largely contained to AJW’s 90s peak and a fair amount of late 2000s/early 2010s indie stuff — but I do know that this conception of herself was neither a reinvention or a return to form. She was, at one point in time, the biggest babyface act in Japan, the sort of person you could build a promotion around. So she did, and she wasn't fucking around.

Things start off heated, with Dynamite Kansai trading shots against rival/partner Mayumi Ozaki. Oz, man. I love her. She is the smallest woman in this match by some measure, and she is completely unashamed to explore the imbalance between herself and Kansai and Nagayo. She’s an incredible physical storyteller, completely devoid of ego, eating shit when Kansai lands a kick flush upside her head, unafraid to look weaker than everyone else in the match when her own strikes land without much effect. She’s a nuisance, a pest, a mosquito drawing blood here and there and flying away just before the killing blow lands. Her tactic here is to kill Kansai and Nagayo with 1000 cuts, not to stand toe to toe. The first minute of action between her and Kansai sets the tone immediately — one shot may put Oz down, but she’s hardly defenseless.

I know that the big draw to this match is the first time Chigusa Nagayo tags in, but in order to properly give that its due, I need to spend a minute on Devil Masami. There is no getting around the fact that she is working an Undertaker gimmick here, and that she’s way, way better at it than ol’ Mean Mark Calaway. Without the supernatural zombie pretense, she’s an emotionless killer, someone it’ll take an entire arsenal of insane wrestling moves to take down, and having already been the terror of women’s wrestling in the 1980s until her forced retirement, she’s earned it. You’d put the comparison to the side entirely were it not for her attire and the occasional sit-up out of a pin — she’s operating on Halloween logic, completely unbothered when she accidentally gets Nagayo tagged in, enduring a death-level barrage of double-team moves from Nagayo and Kansai without so much as blinking. Blinking is Ozaki’s job.

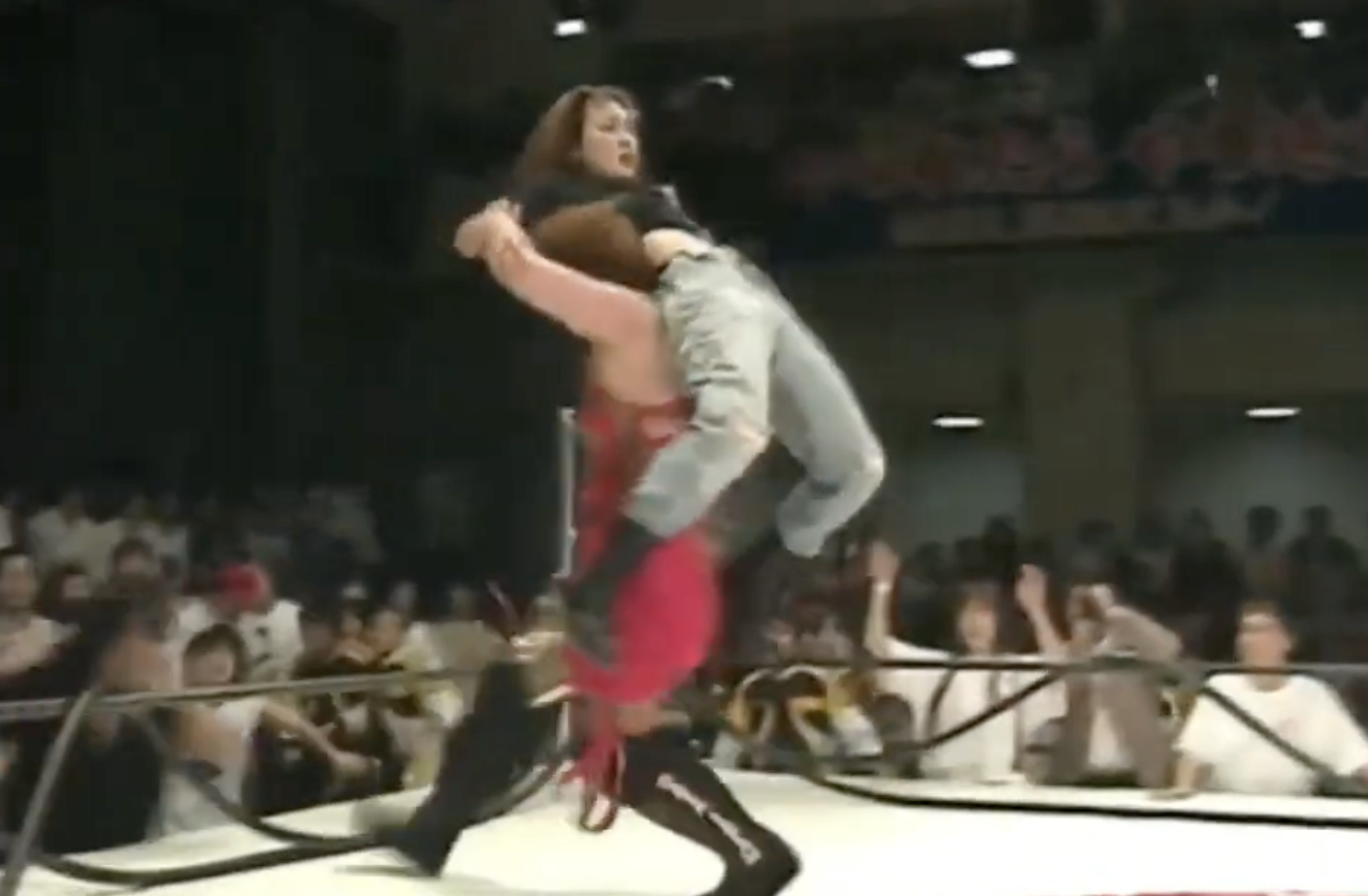

Nagayo is, of course, resplendent. That three years were cut from her career is deeply unfair, but it’s something of karmic revenge that her return, initiated by AJW, led her to this point, teaming with a wrestler in Kansai who was rejected from the AJW dojo and wrestling against Masami, who’s age-mandated retirement match she wrestled in, and Ozaki, who also came from outside the AJW system. She is thrilled to be here. She and Kansai come alive in the violence they dish out, practically competing with each other to see who can lock on the snugger choke on Oz. She’s a somewhat mean-spirited babyface, measuring Oz for a withering kick before snapping her over with a suplex, but it works because she’s showing you what she, and by extension her promotion, will be about. This is what was taken from you. This is what’s being given back. It is 1995 and we are feasting.

Having now offered my feelings on the first five minutes of this match, I’m going to spend the rest of this essay meditating on a point I brought up towards the end of the stream I did with Joseph a couple of weeks ago, about how difficult it’s going to be for me to think about GAEA in a quote-unquote “critical” sense. Though I am probably the least adventurous wrestling viewer amongst my friends and peers, I’d wager to guess that I’ve seen more than most, and that it is actually pretty impressive when something I’m new to wins me over as thoroughly as this match did. I love brawling, particularly 90s brawling, and oh my God does this deliver, successfully hybridizing the kind of violence that made Nagayo such a sympathetic figure with the plunder-based brawls of FMW, IWA Japan, and W*ING. There are billed dog collar matches where the wrestlers involved, months of hatred and blood and bile between them, don’t work the chain as ruthlessly as Masami and Ozaki do early in this match, choking Kansai like the only thing they want more than a win is to literally murder her. Rather than moan about the chain around her neck to the referee, Kansai fires back by winning a game of tug of war and drilling her former partner with a gnarly back drop suplex.

The teamwork, too, is exquisite on both ends, Masami’s rugged disregard for Ozaki playing just as well as Kansai and Nagayo looking out for each other. A lot of love has gone into reevaluating and modifying Southern tag team wrestling as a genre, but I’d suggest GAEA as a promotion ripe for crate-digging wrestlers looking to add dimension to their work. The bit where Nagayo is losing a test of wills to Masami and Kansai supports her teammate from the apron by pushing against her with her foot? The difference between Masami’s slow, measured response to her teammate being locked in a Nagao choke and Ozaki’s frenzied one? Entire relationship arcs are spelled out in these moments, to say nothing of how they escalate the stakes.

When the match breaks down outside the ring, it’s so that Masami can assert herself as one of the terrorizing forces of Nagayo’s life. She leads her through the crowd, bleeding and gasping for air, at the end of a chain, which she then uses to add a little heat to her lariats. There’s a tower of doom choke spot. Ozaki gets thrown around like a poor guy who drove all the way out to Center Stage in Atlanta, Georgia not knowing he was booked to go 1:32 against Big Van Vader on a Main Event taping. Masami invents insane setups for both the tombstone piledriver and the powerbomb. The saves are thrilling. The cutoffs are devastating. Sometimes you catch things happening just beyond the focal point of the camera that look more horrifying than whatever’s center frame, which has the effect of making the main action more grotesque. A particularly good example is Ozaki tying Kansai by her neck to the ring post and hitting her with a chair while the camera is focused on Masami’s continued attack on Nagayo. You see Oz’s chairshots, not particularly gross given Kansai’s limited ability to protect herself, in the background of Masami whipping Nagayo into the barricade. With Kansai limp and hanging in the background, Masami and Nagayo violently hurl themselves at each other multiple times before wiping each other out in a decidedly earned double down.

Watching this match for the first time, I felt a few long-dormant gears in my head begin stirring to life, particularly the ones dedicated to extremely important topics like the cinematic language of wrestling. I would be giving GAEA entirely too much credit for anything other than lingering on their big opening drawing card of Nagayo/Masami in the choice to stay on a single shot for the whole of the above sequence, but it’s little, seemingly inconsequential choices like this that seamlessly marry the live and televised aspects of pro wrestling, whereas more elaborate brawling-based setpieces feel staged or take something away from the live audience. GAEA has a hard camera, but when things get chaotic they stay with the cameras on the floor, and things get so chaotic that the home viewer loses track of the wrestlers off-frame, as you might were you there live and found yourself drawn to the action in the ring while a brawl took place at ringside or in the crowd. Left to the murky depths of cinematic space, Devil Masami’s sudden reemergence on the top rope is surprising, her leg drop on Nagayo utterly crushing.

Choices like these are a factor in the finish of the match, too, as Kansai clotheslines Masami over the ropes and brawls into the crowd with her to draw focus while Ozaki begins the work of taking the ring’s turnbuckle down. The camera shows Oz get to work, then cuts to the brawl. When they cut back to the ring, Ozaki is using the turnbuckle to stab Nagayo in the forehead. And then, because we last saw Masami way out in the crowd, her appearance to rescue Oz from a combination powerbomb/chokeslam comes as a shock.

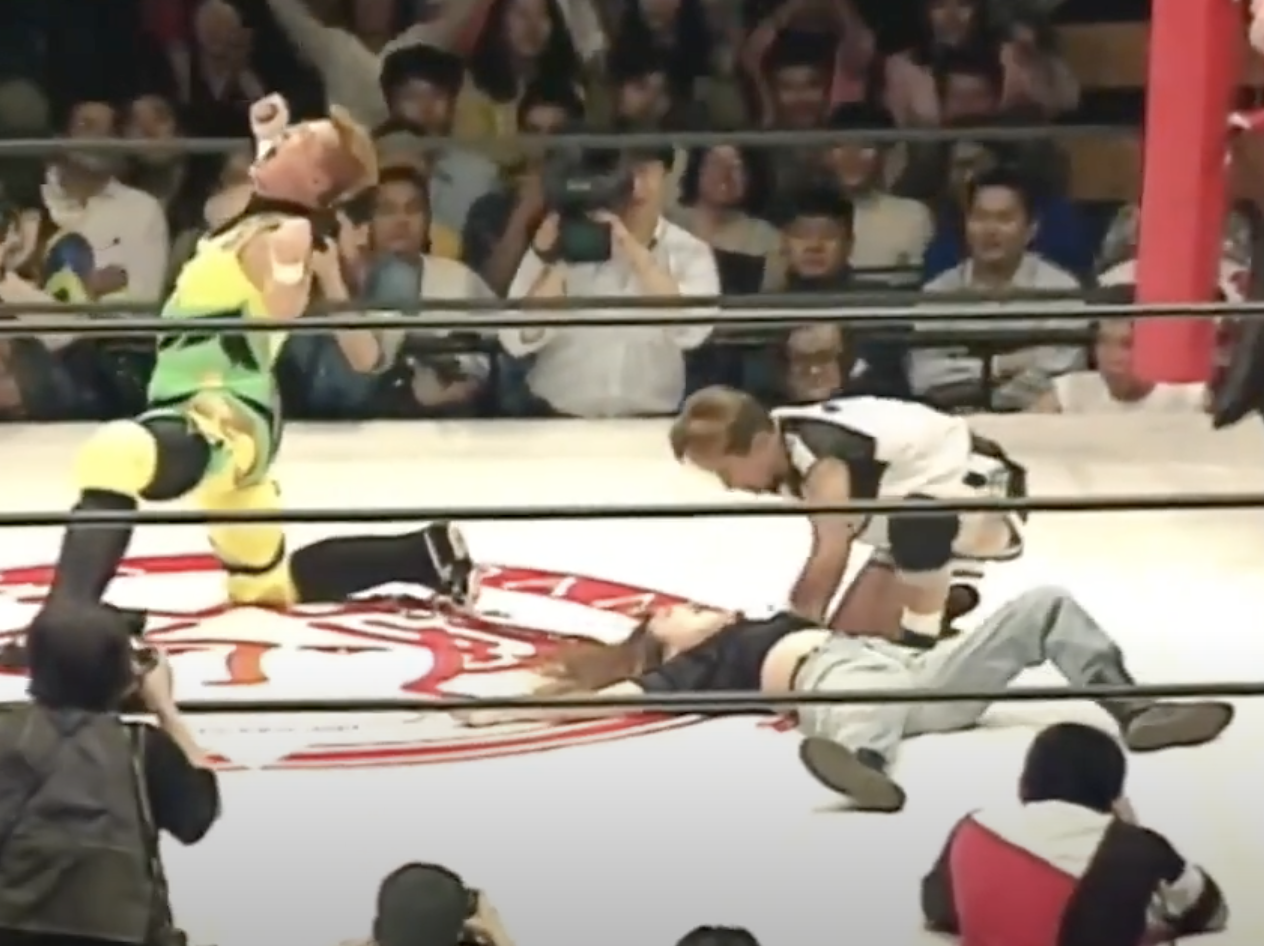

With the ring in ruins and the heels thoroughly finished with the pretense of rules, Nagayo and Kansai try to maintain a semblance of order, continuing to make legal tags to each other despite the lack of ring ropes. Kansai wears Ozaki out with kicks you can hear from the cheap seats, the leg slap a distant dream. Ozaki wasted no time in utilizing the chain she brought to the match, but Masami waits until now to remind us that she brought a wooden training sword with her, which she uses to smash and slash at Nagayo and Kansai’s stomachs. Nagayo in particular is incredible on the sell, and it’s really all Kansai can do to pull Masami out of the ring, finally leaving Nagayo alone with a thoroughly beaten Ozaki. In the background, you can see Masami continuing to assault Kansai with the sword, Nagayo focused on the task of powerbombing Oz. We cut to a closer shot of the powerbomb, definitely enough to put Oz away, but Masami’s reach is long with the sword, Nagayo’s midsection is already battered, and a precision shot from outside the ring breaks the pin up.

Undaunted, Nagayo picks Ozaki up again. Kansai gets a second wind and tries to pull the sword away. We cut to another camera as Nagayo marches Ozaki around the ring for a second powerbomb, losing sight of the struggle over the sword until Nagayo goes to powerbomb Ozaki off the ring, at which point she is straight-up stabbed in the stomach by Masami. This lets Ozaki roll Nagayo up for the win, a bracing and brave decision for the first show of a promotion founded by and built around Chigusa Nagayo, whose talent for inventive finishes is something I am truly looking forward to exploring more as GAEA month continues. Shoutout to every American wrestler with a SAG card and everyone behind the camera who draws inspiration from something other than mid-00s gonzo porn, but the best argument for wrestling as cinema remains bell-to-bell wrestling, shot and edited purposefully.

Rating: **** & 3/4